A professional screenplay is a 90–120 page document where one page roughly equals one minute of screen time, and executives often decide whether to keep reading within the first 5–10 pages. Learning how to write screenplay that lands a “keep reading” reaction is less about magic and more about specific choices: structure you can measure, scenes that change something, dialogue that performs, and formatting that signals you understand the medium.

If your intent is to move from idea to submission-ready script, expect clear constraints and practical steps. Below you’ll find page targets, scene mechanics, genre and budget trade-offs, and a repeatable workflow you can use to draft and revise with purpose.

Frame Your Story With Structure That Serves

Decide the container first. Features are commonly 90–120 pages (comedies lean 95–105; action often 105–120). One hour TV pilots land around 50–65 pages; half-hours 22–35. Streaming platforms can flex, but these bands remain hiring benchmarks. Pick early: your scope influences cast size, number of locations, and the density of plot beats you can afford.

A pragmatic starting skeleton: a three-act shape with measurable waypoints. Aim to hook by page 1, spark an inciting incident by page 10, lock into Act II by around page 25, hit a midpoint shift around pages 50–60, trigger a low point by 75–90, and resolve by 95–110. These are ranges, not handcuffs. If formulas make you rigid, try the 8-sequence model: eight chunks of 10–15 pages, each with a mini-tension curve and a cliff or pivot at the end. Both lenses force you to ask: what changes every ~12 pages that compels the next section?

Anchor the structure to character math: want, need, stakes, and a clock. “Want” drives external action (win the case, escape the town). “Need” alters the internal stance (learn to trust, accept loss). Stakes should be concrete, escalatable, and visible; if they’re only emotional, give them an external proxy (a custody hearing date, a foreclosure notice). Add a time constraint deadlines compress scenes and reduce filler. Interleave an A story (primary goal) with a B story (relationship/identity) so that when one relaxes, the other tightens.

Build Scenes That Do Two Jobs At Once

Every scene should change a value for someone power, knowledge, status, safety so the story can’t go back. If nothing substantially changes, cut or combine. Practical bounds: most scenes run 1–3 pages; a 100-page feature often lands between 45 and 65 scenes. Variety matters: a run of five 2-page dialogue scenes will read flat. Enter late (at the moment of decision) and leave early (right after the turn), trimming greetings and exits that stall momentum.

Mechanically, each scene needs a goal, an obstacle, and a turn. Test it in one sentence: “In order to X, Protagonist does Y but Z happens, so now A is true.” Inside the scene, create micro-turns every page or so new information, a reversal, an escalation which keep readers flipping. Between scenes, favor “but/therefore” over “and then.” If Scene 12 creates a problem that Scene 13 answers with a complication rather than a solution, momentum compounds.

Hide exposition in friction and choice. Instead of stating backstory, make a character pay a cost to get or reveal information. Consolidate beats: a scene that advances plot and exposes vulnerability outperforms separate scenes that do each alone. Plant and payoff are a ratio check: for every significant reveal in Act III, plant 1–2 visible breadcrumbs earlier. Use props and spatial business to externalize subtext (a character polishing an award while belittling a colleague tells more than a speech). If two scenes deliver the same emotional beat, merge or invert one.

Dialogue, Character Voice, And Visual Storytelling

On the page, less dialogue often reads more powerfully. Typical lines run one to three lines of text; reserve speeches longer than eight lines for moments that change relationships or strategy. Strip pleasantries and repeats; “hi/bye,” roll calls, and recaps usually vanish in revisions. Distinguish voices with word choice, rhythm, and POV bias, not quirky spelling. A quick test: hide character names and see if you can still tell who’s speaking. Read aloud or do a table read clunky phrasing, redundancies, and jokes that don’t land will surface fast.

Write subtext: characters rarely say exactly what they mean when stakes are high. Replace direct statements (“I’m scared”) with behaviors and deflections (“Let’s wait for backup,” while checking the exits twice). Use interruptions and overlaps sparingly on the page screen direction will handle the rest but allow sentences to collide when power shifts. Parentheticals (wrylies) should be rare aim for under 10% of lines saving them for counterintuitive readings. Avoid explaining sarcasm; if the line needs “(sarcastic),” the setup may be weak.

Film is visual, so prioritize what can be photographed. Action lines should be specific, concrete, and skimmable: 2–4 lines per block, with white space to control pace. Favor verbs that imply intent (“she edges the door open” vs. “she opens the door”). Avoid camera directions and edit calls (ANGLE ON, CUT TO) unless crucial to understanding a twist; the default is that shots and cuts will happen. Capitalize a character’s name on first appearance and significant sounds or important props sparingly to guide attention without shouting.

Formatting, Workflow, And Industry Expectations

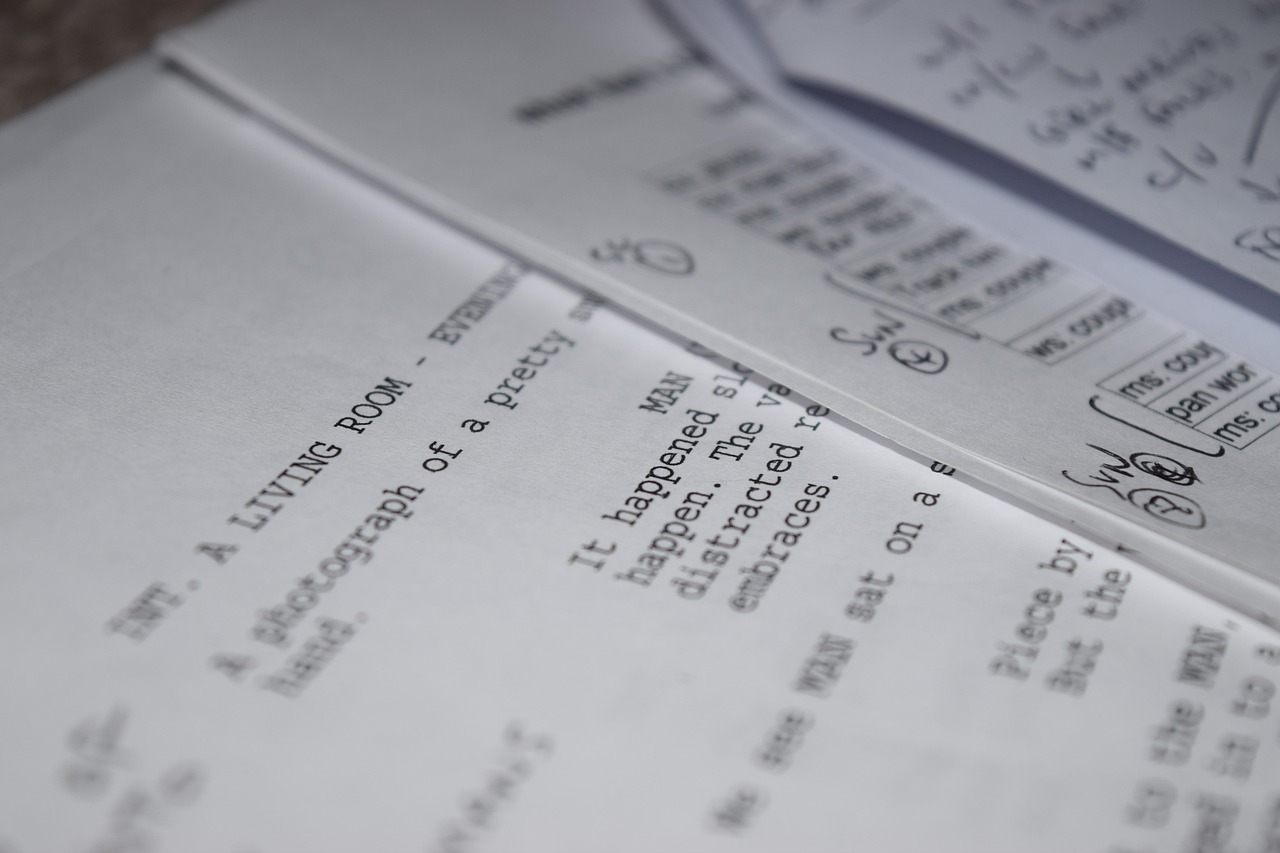

Use standard formatting in 12-point Courier or Courier Final Draft so the page-time heuristic holds. Scene headings (“INT./EXT. LOCATION – DAY/NIGHT”), lean action lines, and indented dialogue are non-negotiable signals you know the medium. Transitions are largely unnecessary; only include when motivated (e.g., MATCH CUT). Export as PDF; include a simple title page (title, your name, and contact). Specialized software handles the margins; reinventing format in Word risks misalignments that distract readers.

Adopt a pipeline that reduces risk and drift. Start with a 25–35 word logline that contains protagonist, goal, stakes, and an irony or twist; if you can’t compress it, the story may be diffuse. Expand to a beat sheet (12–15 beats), then an 8-sequence outline with 1–2 sentence scene cards. Draft at a sustainable pace (3–5 pages/day yields a feature in 3–6 weeks). The first pass is for discovery; do not polish line-by-line. Subsequent passes are targeted: structure (do turns land in the intended ranges?), character (does the want/need conflict drive choices?), clarity (does any reader get lost?), and compression (cut 10–20% dense prose and redundant beats first).

Expect gatekeepers to triage quickly. Many readers decide within 1–5 pages whether the craft is professional, within 10 pages whether the premise engages, and by 30 whether Act II is earned. Common red flags: action paragraphs over 5 lines, excessive parentheticals, wandering scene headers, passive protagonists reacting rather than choosing, and genre-tone mismatch. Know market norms: PG-13 limits on graphic violence and language, R gives latitude but narrows four-quadrant appeal. Budget awareness helps: an indie-friendly script keeps leads under ~10, unique locations under ~25 (favoring interiors), night scenes minimized, children and animals limited, and VFX light. If you’re writing big, telegraph scale with set-pieces spaced ~20–30 pages apart and comps that justify cost.

Conclusion

To move now: write a logline that measures want, stakes, and irony; sketch a 12–15 beat spine; break it into eight sequences; draft 3–5 pages per day without polishing; then run surgical passes for structure, scene turns, dialogue compression, and visual clarity. “How to write screenplay” becomes a system: constrain length, force change each scene, let character need collide with want, and cut anything that doesn’t move time, plot, or power.